* This is an article I wrote probably in late 2007 for the music magazine Mess + Noise, but which now appears to have disappeared from the internet (although it did appear in a print edition, I now gather from old emails), so I figured I'd repost it here as it was a lot of work, is not terrible, and there has been a little interest on social media (see screen caps at the very end). (Note this is the version I sent to Mess + Noise, it might have been edited further before being published, the only thing I did to this was correct the ridiculous mental-block-derived-glitch of misspelling Garry Gray's name a few times).

Consensus suggests as well that he always wore white and was short, bald, and prone to rock 'n' roll excesses. He was the most unlikely godfather to punk rock imaginable, though if that was the mantle he was seeking, it soon became clear that few were going to thank him for picking seven arguably young 'n' aggressive groups from round the country to sign to his record label. The year was 1978. He was Barrie Earl. The label was Suicide. The bands were Teenage Radio Stars, JAB, X-Ray-Z, The Survivors, Wasted Daze, Negatives and the Boys Next Door. The one album released was the compilation Lethal Weapons.

The dying days of the Whitlam government had seen the way paved for public broadcasting, and at the same time the long-established ABC was continuing to reach out – as it had long done in often fairly haphazard ways – to the youth market. Yet the late 70s, according to Bruce Milne who was twenty in 1977, were a frustrating time for anyone who “didn't like prog rock or mainstream stuff. There was nothing exciting. You would read with such envy what it was like musically in '65, or the 1950s.”

Groups that would later seem to naturally come together under the 'new wave' umbrella had already been around for a while. In Australia, that meant Garry Gray and Chris Walsh's bands (Judas and the Traitors and later, The Reals) in Melbourne, JAB in Adelaide, The Saints in Brisbane, Radio Birdman in Sydney, Slick City Boys and Pus in Perth, and no doubt more. None of these people seemed to know about each other, or see themselves as anything but musical outcasts, until a unifying movement was identified by the media: 'punk rock'. By 1977 it was seen as an international – initially, many saw it primarily as British – phenomenon. A small coterie of Australian 'punk' groups, some of which had barely changed for years, some of which had stripped back their sound for the sake of seeming/being new and cool, began to be identified. The punk experience was replicated everywhere, spontaneous enthusiasm fired by awareness of the international movement. Many punks in Australia read about punk in foreign magazines and imagined what it was like – even tried to replicate it musically – without actually having heard it. The imagined version was often better than the real thing, and often blended well with it.

Milne recalls that in Melbourne, the punk scene got a shot in the arm when Keith Glass Band, or KGB, got a residency at the Tiger Room in Richmond. The group played a lot of exciting, obscure 60s covers - anathema to contemporary mainstream rockers who wanted to forget that archaic nonsense - and asked young local groups to support them. “That became the essential night to go out,” says Milne. “The Boys Next Door and Teenage Radio Stars had their first gigs. It was the meeting of the very, very small Melbourne punk scene. Sports were another important band, partly because they were basically playing R 'n' B, but they gave a lot of supports to punk bands too.”

Milne became close to one group in particular, The Babeez, who changed their name to News in 1978. The Babeez rented a run down weatherboard house in Faraday Street in Carlton. The house became a focus of Melbourne punk, and when Melbourne's first punk festival, Punk Gunk, was in danger of being cancelled because the hall that had been booked was withdrawn at the last minute, the festival was held in the street outside the Babeez house. Teenage Radio Stars (then known as Spred), Babeez and the Boys Next Door all played.

Paul Norton, who had a top ten hit while being managed by Earl ten years later, recalls him “with his cowboy boots, Indian jewellery, messy hair, drooping moustache and a three day growth, sort of a scruffy David Crosby.” Author Clinton Walker, who ran the punk fanzine Pulp with Bruce Milne (see Walker’s Inner City Sound for a 1978 tirade against Suicide) says “I'm sure everyone's impression was that he was just some hippy hustler, I mean he had a beard, and that was reason enough back then for eternal contempt.” Ash Wednesday, who played synthesiser in JAB, remembers Earl as owning “a sports car which sagged in the middle when he got into it”. Chris Walsh, bass player for The Negatives, speaks of a man “5 foot nothing, shirt unbuttoned down to his belt-buckle and massive amounts of bling.” Eric Gradman, who played in a number of hip 'Carlton' bands in the mid- to late-70s, recalls a “short, balding, energetic” man with a “rough charm”; Gradman also recalls fighting with Earl, but doesn't remember what the fight was about. Norton concedes Earl was “likeable enough”.

No-one seemed to have a picture of Barrie Earl back in 2007 but here he is, photo by Adrian Barker, stolen from Punk Journey in 2020

Barrie Earl must have looked ridiculously conspicuous in the crowd but he was probably the guy with the biggest plans at Punk Gunk that day. He'd been involved in music festivals, and management, for at least a decade; he'd managed New Zealand group The Cleves, and Mississippi, as well as the legendary blues singer Wendy Saddington. According to Wednesday, Earl’s cavalier attitude to Saddington’s career was far from professional. “He had the reputation of getting acts to a certain point and then not being able to take it any further,” recalls Norton.

In the mid-1990s James Freud, the vocalist in Teenage Radio Stars, was interviewed for Kimble Rendall's Mushroom Records twentieth anniversary special, Counting the Beat. He recalled that “Michael [Gudinski] has always been fairly progressive, and he had this guy Barrie who'd just been hanging out in London and came back and said this is where it's at and Michael said OK let's do a punk label and they did… We did one record and it was a bloody disaster.”

In 1978, Bohdan, the singer, guitarist and the original 'B' in JAB (Johnny, Ash, Bohdan – second guitarist Bobby Stopa and bass player Pierre just confused the issue when they joined) told Juke magazine that JAB had got involved in the label because, having heard someone was planning to release some 'new wave' records, he “thought I'd just come and see him.” Earl was up for it. Wednesday recalls “We went round for the pre-signing talk at Barrie's apartment in South Yarra. There's a white fluffy carpet, nice white fluffy lounge, a white afghan hound, and a nice human lady incarnation of the hound. Barry gave us a tacky initiation speech; it was all "hundreds of thousands, hundreds of thousands, money money money"; he behaved as if he was right in there at the pulse and he knew what was happening…”

JAB had relocated from Adelaide a year previously; their formative period had been extreme, with many of the shows they put on in the hills ending in violence and brutality amongst their fans and followers. Michael Gudinski's mettle was, surely, tested the first time he saw the group; Earl took him to see them rehearse near the Mushroom offices and, says Wednesday, “there we were, not really sure he was going to show up, Bohdan was in the full SS get up, singing 'jab jab jab it to death'. I had a few iron crosses on my shirt too. It was all the shock value; our knowledge of German history was molded on Hogan's Heroes. There we are and the door opens and Michael comes in and stands there nervously laughing...”

“I don't know if we were really a punk band,” adds Wednesday. “It was synthetic shock rock. Anything that was taboo was ok with Bohdan, and he wanted to be noticed at any cost. We'd evolved independently of punk.”

“We certainly weren't into punk,” agrees Stopa. “We didn’t try to look like a cohesive thing although Johnny tried to get me to change my name... I wasn't going to change my name to some ridiculous thing I'd be embarrassed about five years on. Most of the guys on that record, you couldn't really call punk. Guys like Rowland Howard and Nick Cave they were upper-middle-class. It was all theoretical to them.”

Another Adelaide import to Melbourne's punk scene was X Ray Z, regarded by many as dubious because they were, through no fault of their own, a few years older. They'd come together as Rufus Red, “a more melodic style band, really, which had kind of evolved in the early 70s”, says their guitarist, singer and main songwriter Peter Doley. Some close to the band compared Rufus Red to Split Enz; they were theatrical and dressed up for shows. Their drummer, John Wilkinson, “came into it with a deep background in modern jazz – this led to the arrangements being complex and interesting; the lyrics were always a story, that was Peter's thing, he always had a story to tell,” Wilkinson recalls. In Melbourne they were briefly represented by Jon Blanchfield, who'd released some of Lobby Loyde's great mid-70s solo albums, and Blanchfield and Wilkinson found a way for the group to record some demos. The next step, according to Doley, was to “scratch our way in playing shitty little gigs. Then we were chucked out into the wilds of Melbourne, going through Premier Artists. We changed in response to what we saw; we realised that the softer stuff wasn't the go, and we got a harder edge.

“It was a case of getting a bunch of new songs and just 'play as fast as you can!' We copped a bit of flack for being pseudo-punk. I would have been thirty at the time, which was certainly old compared to the Boys Next Door. But we were all exposed to punk stuff. The credo that ‘everybody can have a go’ was really quite prevalent, and everyone was banging away these funny little bands chucked together making horrible noises. It was quite lively.”

“I really liked the new direction,” says Wilkinson now. “I was very fond of Rufus Red, but we'd picked up a bass player in Adelaide called James Lloyd and he came to Melbourne with us, and James and I had a nice rhythmic brotherhood there. I wanted to tighten up the rhythm section and give it a punchy sound, rather than before when it was a bit waffly.”

X-Ray-Z made a rugged, bolshie EP for Mushroom records, 'Poor Image'. Somehow this – and the connection with Gudinski's Premier Artists booking agency – saw them shifted sideways to become a member of the Suicide Records family.

There were seven Suicide bands, and only two of them didn't live in Melbourne. Sydney's Wasted Daze are somewhat mysterious, though main guitarist/singer Terry Wilson had been a member of the late 60s progressive group Tully. The Survivors were legends in their home town of Brisbane, a highly popular and adept band whose sets were mainly cool 60s covers. Their contribution to Lethal Weapons was a single that had already been issued by the band themselves, and a multiple-album deal came to nothing. With 2007 hindsight, the biggest bands on Suicide look like the Boys Next Door – whose recordings for the label would be the group's first release – and the Teenage Radio Stars, Suicide's pop hopefuls who brought Sean Kelly and James Freud, later of the Models, their first wide exposure.

The Boys Next Door's, and the Teenage Radio Stars', tracks for Lethal Weapons are probably the weakest on the record. The first band were, perversely, covering Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazelwood's 'These boots were made for walking', alongside some fairly straight punk songs, 'Masturbation Generation' and 'Boy Hero'. The Boys Next Door’s charismatic singer Nick Cave spoke appositely, however, when he told an anonymous Juke journalist in May 1978 that record companies had “thought the punk thing was just a fashionable craze. They didn't understand it was just new groups who'd be making music for a long time.” TRS (as they were often called at the time) had probably been retitled with a name nicked by Earl – there was a fairly prominent group in England at the time called Radio Stars – and he then coerced them into rewriting, almost note-perfect, a song by the British group The Vibrators, 'Baby Baby' as 'I wanna be your baby'. Earl was audacious to suggest this but the song itself – in either version – is hardly earth-shattering; Sean Kelly's lyrics are amusingly lame, and the stuttery guitar line stolen from 'Sweet Home Alabama' is catchy, but that's about it. The group's other tracks have more appeal.

1978 wasn't over before James Freud had told the world that the Teenage Radio Stars' punk outlook was just a pose to get their foot in the door. But there was one band on Lethal Weapons who were probably the most genuine, and the most short-changed. The Negatives' Garry Gray told the same anonymous Juke journalist that he'd been trying to get his band going somewhere for years; the group, which also featured Chris Walsh, a uniquely original and creative rock bassist, and drummer Peter Cave – not Nick Cave’s brother – had emerged from the wilds of Mount Waverley.

“You could call us the Mount Waverley three,” says Gray. “Chris Walsh, Tracy Pew, Garry Gray. I met Chris at primary school, Tracy at Sunday school. When we got to be teenagers in the 1970s, Melbourne was the most boring, predictable place on the planet: Mount Waverley was the epitome of The Stooges' "No Fun". Straightsville, a bunch of squares...except for us guys.... We set about making it a whole lot more interesting and our insatiable curiosity for music took us exactly to where we dreamed of going...more or less.”

Gray is planning to issue a lost album by the pre-Negatives group, The Reals, which he describes as “one driven focused thing.” This band had featured Ollie Olsen, who changed their name and, necessarily, their line-up when Olsen decamped to form the Young Charlatans with Rowland Howard. Howard's band The Obsessions, Bruce Milne recalls, were due to debut alongside the Reals (not to be confused with Dubbo group The Reels) and the Boys Next Door at a show Milne had organised at Swinburne Tech. Milne recalls the Suicide label as “half baked”, adding “I was suggesting to bands I liked that they should see a lawyer. The Babeez, they were probably called News by then, took the meetings but basically decided they would stay independent.”

Gray says now that his reaction to being signed to Suicide was “totally naive. I saw it as normal. I think we were playing at the Tiger Lounge and Earl came up and said, "I can make you a star" or something... and we said, ‘yeah, right, you know where to find us.’” Walsh believes that it was obvious from the outset that The Negatives were brought in purely to make up the numbers, and that TRS and the Boys Next Door were the only bands Suicide, Earl and Mushroom were really interested in.

Wasted Daze did Bo Diddley covers, and the Boys Next Door were also covering a song (as were TRS, let's face it). Earl, Gray recalls, “wanted the Negatives to do the Roky Erickson single "The Interpreter".....great song, but the fact that we were told to do someone else's song was like waving the red flag of rebellion at Chris and myself....we'd been working for a few years on original material and had no intention of releasing cover songs as our first record.” Instead, after a few unsuccessful attempts at recording live favourites like ‘Nothing to Say’, they recorded a slow and atypical original, 'Planet on the prowl'. It was over six minutes long, probably the reason the Negatives were the only Lethal Weapons band to get just one track.

For reasons unclear a number of the tracks on Lethal Weapons were produced by established musicians. The best-known, and probably strangest, pairing was Skyhooks' Greg Macainsh and the Boys Next Door; the last of the 70s Skyhooks albums, Hot for the Orient, tilts at the 'new wave'. Eric Gradman, who'd been a friend of Gudinski's at school but more importantly a well-known performer in Melbourne's mid-70s underground bands like the Sharks, the Bleeding Hearts and later Man and Machine, was brought in to produce 'Planet on the Prowl', which Gray says “wasn't very representative of the Negatives – it was representative of Eric Gradman.” Gradman now responds equivocally that no doubt participants had their “own (incommunicable) mental picture… I remember recording them as raw sounding as I could manage and then STRUGGLING to meld that with a (my) kind of psychedelic/B movie aesthetic… I remember Garry being sullen and uncooperative; [perhaps] I was trampling his garden.” The Negatives, says Walsh, didn’t hear Gradman’s final mix of their song until the album was released.

Mike Rudd, best known as the man at the centre of Spectrum and the recently-defunct Ariel, produced JAB's tracks. His explanation of his involvement shows the ways in which Lethal Weapons was an element in a wider network in which Earl and his erstwhile business partner Phil Jacobsen were the starmakers.

“When that album was being mooted,” recalls Rudd, “I imagined that I'd retired from gigging, so somebody at Mushroom/Suicide thought I should get involved in producing one of the bands. It turned out to be JAB. I was a novice as a producer, and I think it was JAB's first experience as a band in the studio too... I thought Bohdan was (mostly) very funny, but with humour running somewhat counter to the original premise of punk, JAB's lifespan was always going to be limited. The recording was pretty rushed, but I'm not sure that more time would have benefited the tracks.”

Rudd describes Earl as “a poseur hairdresser who affected a cockney accent and went to bed with his boots on. He adored hanging round with musicians and the music scene in general, and when Ariel was in London, he was our manager Phil Jacobsen's guide and advisor… Barrie had an unfortunate knack of eventually getting up everybody's nose. He talked me into getting a most unfortunate perm at a London hairdresser's.' Rudd has, however, maintained a friendship with Jacobsen.

Bobby Stopa remembers Rudd's work on JAB's songs as 'fine… I don't know if he really brought out the best in the band, it didn't exactly sound the way we wanted. I don't think the Boys Next Door’s songs were very good either, the whole album was pretty ad hoc!”

Engineer for the majority of the tracks on Lethal Weapons was Michael Shipley, an Australian with recent experience working with the Sex Pistols – who has since gone on to become a world-famous record producer. Wednesday remembers that Shipley told him that John Lydon/Rotten had wanted to put tape loops and synthesisers into the Pistols' mix – a little like the way Wednesday used such sounds in JAB – but that Malcolm McLaren wouldn't let him.

X Ray Z “recorded our tracks pretty quickly”, says Peter Doley. “It was all done on the cheap: we recorded over 2nd or 3rd generation tapes - Someone said Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs at Sunbury were on them. We had to mix it really quick because the tape was dropping out!”

The group's 'Three More Glorious Years' (incorrectly credited on the sleeve as 'Three Glorious Years') was a classic political anthem, written by Doley in disgust at the Liberal party's win that year. “A fair few of us were bearing the brunt of Fraser's dole queues,” he says. “It's a satirical send up of the chosen man. I'm still writing a few songs like that, and of course Howard's the latest version…”

Lethal Weapons is a queer fish, right down to its presentation. The cover image – blood oozing from a gun – is bizarre, and the credits are so convoluted you almost need a pen and paper to work out which tracks were recorded by whom (the 2007 reissue corrects this absurdity with a straightforward track listing). The original LP was pressed in white vinyl as a limited edition (Chris Walsh and Garry Gray turned theirs into ashtrays). The second pressing – in ordinary black – was, in fact, far more limited because, despite a strong press advertising campaign, the album failed to sell. The Teenage Radio Stars' 'I wanna be your baby' was released as a single, and the group played some interesting supports, such as an unlikely Skyhooks show in August.

There were a number of Suicide package tours into Adelaide and Sydney. Dave Graney, who moved to Adelaide from Mount Gambier in the late 1970s, remembers seeing a show in Rundle Mall. “It was X Ray Zed, the Boys next Door and the Teenage Radio Stars,” he says. “X Ray Zed were a little bit older and had the heaviest sound… The Boys Next Door were Nick, Mick, Phil and Tracy. Rowland hadn't yet joined. Mick had a white trench coat on and was playing his Maton guitar. Tracy had a Rickenbacker bass (very modern at the time) and someone had that piano key tie on. They did ‘Boots’ and ‘Masturbation Generation’ and ‘Earthling in the Orient’ and probably ‘Boy Hero’ along with some covers and other songs. ‘Sex Crimes’? They were great then. Brilliant performers and I saw them every time they came to Adelaide… Teenage Radio Stars had more barre chords and heavier sounding guitars. And dyed blonde hair. I remember their version of that Vibrators song.

“A couple of years later we were in Melbourne playing with Chris Walsh who was in the Negatives. Their song, "Planet on the Prowl" was the most interesting on the actual Suicide album.”

If the way Suicide came together under Barry Earl was spectacularly fast, the way it fell apart was similarly dazzling. Lethal Weapons was released in March 1978; by the end of the year, JAB had split, Barrie Earl was managing James Freud and the Radio Stars which was, effectively, Freud and a whole new backing band; the Negatives were finished, with Garry Gray decamping to Sydney to, he now says, get away from hairdressers. The other groups soldiered on in various forms; X Ray Z changed their name again, to the Popgun Men. Models – the group formed by Ash Wednesday and manager Karen Marks and featuring ex-TRS member Sean Kelly, JAB's Johnny and Ash and, before long, crack bassist Mark Ferrie – were already hugely successful on the live circuit by December of that year.

The Boys Next Door had recorded an album for Suicide, Brave Exhibitions. As its release date dragged on they became a Suicide group no longer (there was no announcement of the label's demise – just the obvious fact it was over) and were instead co-opted into Mushroom. They appealed to Gudinski to let them scrap half the record and record five more songs showcasing the talents of their new member Rowland Howard, and released their first album as Door, Door. Keith Glass was managing them and later released their records on his label Missing Link, during which time of course they became the Birthday Party. In many ways, Missing Link picked up where Suicide left off.

Dave Graney and Clare Moore moved to Melbourne from Adelaide in the late 1970s. “Around that time”, says Graney, “you'd go to parties and there would be these characters who had this brooding cloud about them. Ex-members of Jab. The Suicide records experience seemed to colour the attitude to the music scene of everybody who was involved. They all had this "bad shit" in the background. It gave some people an "out" so as to stop them from ever trying anything again.”

Ash Wednesday says of the album: “I guess it's OK. Half the groups on it are really far from punk. It was really scraping the bottom of the barrel to come up with something that was supposedly new wave.” Bobby Stopa is sure that Suicide wasn't “going to have anything more to it - it was basically a subsidiary to Mushroom, and they were probably just trying out bands.” Chris Walsh has the same feeling: “Mushroom was making sure there wasn’t money to be made out of this punk rock thing. They didn’t understand it, but they didn’t want to let it escape.”

Ash Wednesday says of the album: “I guess it's OK. Half the groups on it are really far from punk. It was really scraping the bottom of the barrel to come up with something that was supposedly new wave.” Bobby Stopa is sure that Suicide wasn't “going to have anything more to it - it was basically a subsidiary to Mushroom, and they were probably just trying out bands.” Chris Walsh has the same feeling: “Mushroom was making sure there wasn’t money to be made out of this punk rock thing. They didn’t understand it, but they didn’t want to let it escape.”

Counting the Beat contains a brief segment on Suicide in which Gudinski announces that “The label achieved… nothing.” But Lethal Weapons has become notorious. One of the most extraordinary aspects of its story is that Mushroom's arty arm White Label saw fit to reissue it a mere five years after it first appeared; it was already becoming legendary. Now, Aztec have reissued it with one extra track – a TRS b-side – and spectacular sleevenotes.

It's a peculiar, and in many ways misunderstood chapter in Australian rock history. The artefact itself is fascinating enough; the stories behind it just add to the appeal. Putting aside for a moment the fact that, for many of the 44 people listed on Lethal Weapons' sleeve, this was to be the first (and in some cases most regretted) step in a luminous career, the album itself is diverse and bizarre and, in parts, pretty good. It captures a fractured array of scenes and styles, opportunists rubbing shoulders with great talents who in many cases didn't do much more, under a makeshift banner created by the industry and which at that moment was going by the names ‘punk’ and 'new wave'. It's not representative of a scene, and its derivative elements are more to do with the record industry trying to mould artists into something they could market, rather than a dearth of ideas. Once you take that on board, you can enjoy the ride like you would a shonky ghost train, or movie with hokey special effects, or perhaps, just perhaps, a compilation album with six or seven really good tracks. A trip and a treat.

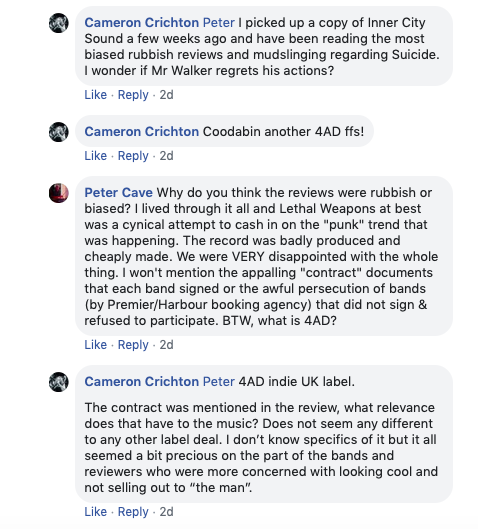

Coda: from the 'I got drunk at the Crystal Ballroom' facebook group, April 2020:

2 comments:

These are genuinely wonderful ideas in regarding blogging.

You have touched some fastidious factors here. Any way keep up

wrinting.

No-one but no-one is every going to stop me wrinting

Post a Comment